|

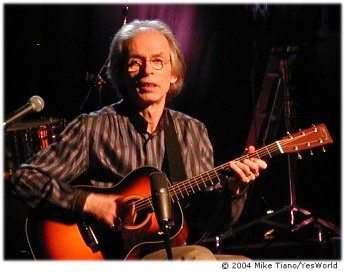

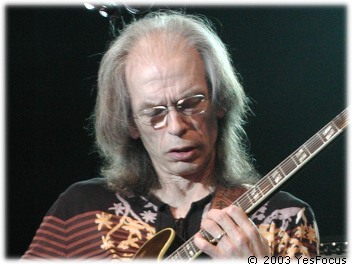

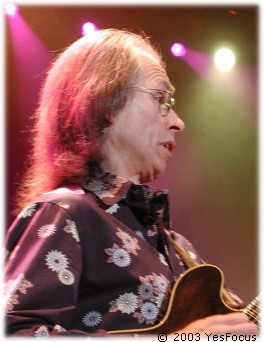

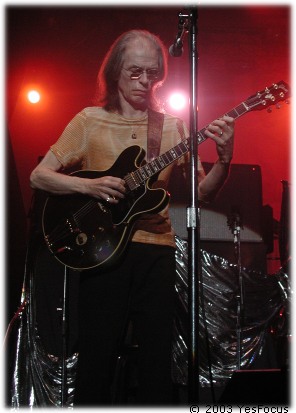

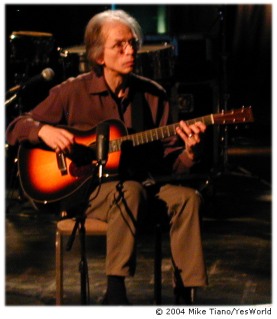

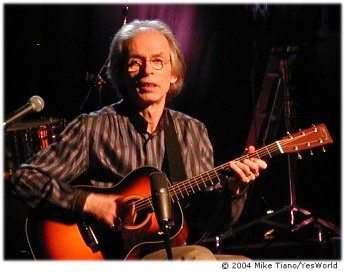

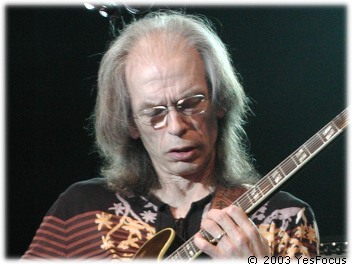

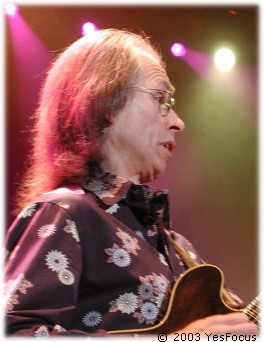

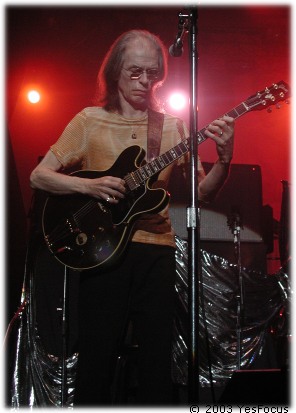

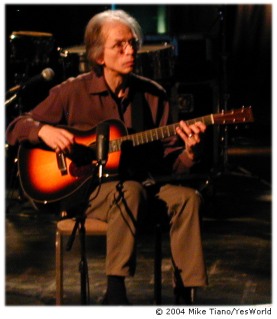

Steve Howe's

recent release ELEMENTS is his most eclectic in years. Running the

gamut of musical styles which has been a trademark of Steve's over his

long career, it introduces a band concept, Remedy. Under that moniker

Steve recently toured Europe with a band that included his sons Virgil

and Dylan, performing selections from many of his solo releases, most

never before performed live. A possible American tour may occur later

this year.

Following our

conversation on Yes in

NFTE #285 we

discussed the album at length. This issue features the conclusion of

that conversation. Playing the album as you read Steve's comments is highly

recommended.

MOT

MOT: Let's move onto a very exciting portion of this

conversation, and that is to talk about your excellent new album,

ELEMENTS by Remedy. Let's set the record straight here.

SH: Yeah...

MOT: How does this Remedy concept differ from a Steve Howe

solo album?

SH: (Laughs) Well, I guess it's not so

much in the way that it's constructed as much as it's the way that it

ends up being. The way this record ends up being is I do what it says

on it, I play the guitar basically, and besides the vocals and what

guitar means to me is a whole lot of guitars, which it is as well; but

in the most part, I'm presenting more of a straight-ahead front of

either being a guitarist, or singer/guitarist on three tracks. So

although there's little stabs at this during the solo albums before, a

lot of the time certainly in recent years, I've done a great deal more

myself and presented that as a finished product. Feeling that I wanted

to go on stage was an inevitable thing I've just got to do with my

music, my solo music with a band, then making the album and not

inviting people in, not getting them involved would be a lost

opportunity. As I started thinking more about having lots of people

play on the album and alleviating me of multi-responsibilities other

than the guitar, and that really excited me, so I figured that maybe

it was justifiable to call it a band name like Remedy, I mean it's

only we're having a go at it and see how it runs, and I hope that it's

going to be able to prove, maybe in the next couple of years, the

opportunities to do that as a touring band that we can sort of build

on it. SH: (Laughs) Well, I guess it's not so

much in the way that it's constructed as much as it's the way that it

ends up being. The way this record ends up being is I do what it says

on it, I play the guitar basically, and besides the vocals and what

guitar means to me is a whole lot of guitars, which it is as well; but

in the most part, I'm presenting more of a straight-ahead front of

either being a guitarist, or singer/guitarist on three tracks. So

although there's little stabs at this during the solo albums before, a

lot of the time certainly in recent years, I've done a great deal more

myself and presented that as a finished product. Feeling that I wanted

to go on stage was an inevitable thing I've just got to do with my

music, my solo music with a band, then making the album and not

inviting people in, not getting them involved would be a lost

opportunity. As I started thinking more about having lots of people

play on the album and alleviating me of multi-responsibilities other

than the guitar, and that really excited me, so I figured that maybe

it was justifiable to call it a band name like Remedy, I mean it's

only we're having a go at it and see how it runs, and I hope that it's

going to be able to prove, maybe in the next couple of years, the

opportunities to do that as a touring band that we can sort of build

on it.

MOT: To reiterate, it's not a matter of you just have these

songs, you just bring these other people into play on them. It's just

you were a unit of the same people played on all of those songs and

you work on it together as you would have a band.

SH: Well, that's an exaggeration to say

that, because as I started out by saying, I said to you that this is

Remedy. This is a band, not so much in the way it was constructed, but

more in the way that it ended up being, in that my role is the

guitarist. I did map out a lot of things, and then we invited people

to play, and it kind of changed, so I don't know. I used the key way

of my writing method in this record; I've used that way that I record

stuff, and then the way that what's different is the way that I

elaborated it, not so much myself, but by bringing in and forming

around me a semi, quasi-fantasy virtual band, you know what I mean

(laughs). It's a bit of everything; it's a kind of idea, if you like,

as much as anything else, and it doesn't necessarily have to be a

five-piece or a ten-piece or it could be a three-piece. In my mind, I

would be helping to build that idea of me and other people who've got

interesting things to do, but my music is the main carrier, if you

like.

MOT: As I think I said to you earlier, it's a very eclectic

album, and is in some ways harkens back to THE STEVE HOWE ALBUM.

SH: Right. That's interesting. I hadn't

really thought about it like that. What, because it's got minimal

songs, and it's got like I suppose THE STEVE HOWE ALBUM had, if you

can call it country "Cactus Boogie", a sort of ragtime sort of thing,

I suppose you can, then there is a quite a mix on that album. Yeah,

but there is orchestra. I mean, and there is Spanish guitar, so I

think...

MOT: Different styles.

SH: THE STEVE HOWE ALBUM's got much

broader strokes, and I'm trying to lessen that breadth on records that

I make. That's partly why I did PORTRAITS OF BOB DYLAN, because I had

to really tight constraint to work within...

MOT: Dylan and Virgil definitely excel throughout the album.

SH: Good, thank you.

MOT: And their own playing is as individualistic as your own

guitar playing is. What is it, is it just in the genes? (laughs)

SH: (Laughs) Well, it's obviously nice

that you say that. Yeah, there is a certain flair, and intensity. I'll

give you one example: I saw Virgil on stage playing drums, and I've

seen him many times, but one of the last times I saw him he really

did get carried away and he was like drumming, and his head went down

on the side, and then he started singing. I've might have taken years

to be anything like somebody who could introduce me, but he also talks

very relaxed. So he's come out of his shell, but I think Dylan's the

same. When he's drumming he steps away

from the normal world, and Virgil does the same thing too, so I think

we all do that, and that is maybe something in our genes that's passed

on (laughs). I think my dad was a brilliant cook, and maybe it comes

from that, I don't know (laughs).

MOT: When I think about Dylan's drumming on your album

it's his own background which is jazz drumming, and comparing that to

your work with Bill Bruford to where you have a jazz drummer basically

bringing his own sensibilities to a rock setting...

SH: Yes, yes.

MOT: ... and I see Dylan doing that a lot on this album.

SH: I think you're right. I think it's a

healthy thing, I mean when you talking about Rush the other day, I

mean that drummer's really respected as an all-around drummer, isn't

he?

MOT: Neil Peart.

SH: But like when it comes to it, it's

what he does... well, he might have a jazz influence, because Dylan

has loved all those drummers like Bruford, and the other guys that

he's met. Not only the people that he's met through me of course, but

the people that he's met outside of that, and I guess he wants to

learn as much as he can, but his roots are very excitedly in jazz, and

he can't get that out of his system (laughs). He doesn't want to; it

is his system, if you like. But of course he is versatile that he

plays any kind of drums, but he more and more wants what his heart

tells him, and hopefully through his record and his own shows that

he's been doing, he's shown a lot more courage and bravery to really

kick it in and make it work.

MOT: Not to denigrate the other musicians, including Virgil, but I think

Dylan's contributions to ELEMENTS really help make it as good as it

is, even better than it could have been. You could have gone with

stock drumming in various parts, but he's very

creative.

SH:

That's right. The adventurousness that I think early Yes had, and yet

we used to play more rock than we did after the '70s...but we were playing

really good rock stuff that had the twists, had the what was called

later progressive twists, but we had a jazzy-thinking drummer, and

that was Bill. Dylan has got the same kind of intent going on in his

mind, as you've pointed out, what where he's got those kind of roots

that that's his main thing, and it's not going to change. It's a

wonderful thing, and on this album as you've said he does really

stand out. I think it's become more natural that for this album

he does stand out, and that's why he's got like some short drum break

things in the first track to show that Dylan isn't just present [as

if] he's popped in to play with me. He's contributing a bigger sound

and a more thinking-man's drumming, really, really interesting stuff

all the way down the line.

MOT: Can you talk a little bit about working with Andrew

Jackman on this album and his contribution?

SH: Yeah, really important that sometime

back when I was planning this, and when I wanted some arranging,

Andrew was a natural choice, and I called him. He said "Oh yeah, just

get in touch with me when you need it done," and then it started to

come closer, and he said, "I'm really, really going to do this." He

wanted to play the arrangement, and so he selected the musicians-the

seven brass players on the album. I made him special mixes of both

tracks that he was going to do, and I'll always keep them because

they're quite sentimental now, but they have a variety of different

ways of looking at the same two tracks: four mixes on the each one,

some have like no guitar, some have guitar with no brass, and some

have brass with no guitar, and it's kind of this quasi-mix, so he

could sift through and work out things. Basically what's happened on

"Westwinds", I'd already constructed quite a good arrangement, in fact

it's more or less what's there now, of saxophones and trumpet sounds

on a synthesizer, on a keyboard, and I quite liked them. When I played

them to him, he said, "That is good, that is a pretty damn good

arrangement. Great, I'll score that; I'll write it up, so a real band

can play it." And then the other track ["Pacific Haze"] I said, "Look,

here's a free hand," because I've played this track in a very, very

spontaneous way.

So I recorded the track, got it really good, but I wanted it like

"Westwinds" to be orchestrated, but I hadn't written the

orchestrations; so I said I'll give him a free hand and we'll

do an arrangement on that piece. So he left it quite sparse at the

beginning, then it gradually builds up towards the end. Also

on that track Gilad Atzmon played some

solo sax on it, and it's quite incredible what he

does at the end... but "Pacific Haze" is a very special track,

not only because Andrew scored it and certainly he left us, but it was

a strange twist of destiny that this track turned out so incredibly

good, and had so many contributions from people that I liked. Dylan of

course had introduced Gilad to me, and Gilad's got his own band, and

we should do a little bit of promo for him, but not that he needs it

much. He won best album of the year, best jazz album of the year in

a certain important poll, and he was very pleased about that, so

he's done loads of stuff with Dylan on I think on all sorts of other

music.

But sadly Andrew's fate was never--besides the production of the

recordings--never to hear the finished mix if you like. I was about to

send them to him when he sadly passed away, and that was a very big

lump in my throat, and I thought well that's a shame, because they

turned out so brilliantly. The only reason I hadn't sent it to

him [was] because I didn't have the version with his name on it, but of

course maybe in hindsight I'll never wait to send something to

somebody if you got that feeling. But even at the session, he was

quite remarkable because he conducted the brass ensemble, and he did

that with a certain vigor. "Westwinds" was always really under

control, because we kind of knew what it was. There was a lot of

things to do, but when we did "Pacific Haze" and it was his

arrangement, I remembered his feet start to leave the ground; he was

kind of conducting them, and he was getting so into it. He had a

marvelous way with musicians, because they respected him. He was

amicable; he had good social skills. He could communicate his musical

ideas, not offend anybody. If he had to be critical, he'd do it very

lightly, and say, "Oh please don't do that there," and fascinating

things would happen, like at the end of "Westwinds", he had them

cutting off very quick (sings part of song), so he did it, and I said

"Oh no, ok. I'd love you to hold that last note, because I think... ,"

and it really did fulfill the track so much when right at the end

(sings part of the song), and they hold that chord; just seeing how

quickly things can happen, and everybody feels they're right, just

goes ahead. I said, "Oh, give that note a four-bar sustain." But sadly Andrew's fate was never--besides the production of the

recordings--never to hear the finished mix if you like. I was about to

send them to him when he sadly passed away, and that was a very big

lump in my throat, and I thought well that's a shame, because they

turned out so brilliantly. The only reason I hadn't sent it to

him [was] because I didn't have the version with his name on it, but of

course maybe in hindsight I'll never wait to send something to

somebody if you got that feeling. But even at the session, he was

quite remarkable because he conducted the brass ensemble, and he did

that with a certain vigor. "Westwinds" was always really under

control, because we kind of knew what it was. There was a lot of

things to do, but when we did "Pacific Haze" and it was his

arrangement, I remembered his feet start to leave the ground; he was

kind of conducting them, and he was getting so into it. He had a

marvelous way with musicians, because they respected him. He was

amicable; he had good social skills. He could communicate his musical

ideas, not offend anybody. If he had to be critical, he'd do it very

lightly, and say, "Oh please don't do that there," and fascinating

things would happen, like at the end of "Westwinds", he had them

cutting off very quick (sings part of song), so he did it, and I said

"Oh no, ok. I'd love you to hold that last note, because I think... ,"

and it really did fulfill the track so much when right at the end

(sings part of the song), and they hold that chord; just seeing how

quickly things can happen, and everybody feels they're right, just

goes ahead. I said, "Oh, give that note a four-bar sustain."

Working with Andrew was never difficult. It was always creative...I think when we opened in Japan, I

played "Double Rondo" on electric guitar and said that I played it for

Andrew, and "Double Rondo" was really an amazing thing that we did

together. I'll always love seeing ideas just grow to colossal

size.

MOT: On THE STEVE HOWE ALBUM.

SH: Yeah, very fond of that, and of course

he was on the list in my book for doing MAGNIFICATION as well, because

I think he would have done a wonderful job of that as well.

MOT: Why didn't he, then?

SH: The decision was made [to go with]

Larry Groupè because the project was based in California, he was in

California.

MOT: You know what I'd like to do is briefly go through each

one of the songs.

"Across The Cobblestones": What is it about that

music that evokes home to you?

SH: Well, I'll try to put it in a

nutshell. I guess the lyrics had a staying power with me, because I

wrote them many, many years ago, and maybe not in that form. They were

written more in a long song form where there was lots of words and

there was lots of this and lots of that. I kept thinking, you know the

things I like about this song is this line, that line, and that line,

and I always highlighted them and thought the rest was just really

waffle. And then the other thing happened and I'd stop thinking about

it as that song, and in fact that didn't have the same melody or

structure or anything like that, so there was just some lyrics lying

there. Then I had this (sings opening riff)-I had that maybe four

years ago or something, and I must have played it to Yes once or twice

and said what do you think, and they passed on it basically, so I had

this kind of steel guitar group. It was actually a guitar and steel

playing the same things, and I thought it was sort of a "Going for the

One" sort of sound, it had a sort of rocky feel and all that,

but I coupled it with this slightly more melodic piece that I play on

the old GTR sort of synth-the one we used on there called the GR-700.

I like that sound because it's a nice retro sound, and it's one of the

settings that I like. SH: Well, I'll try to put it in a

nutshell. I guess the lyrics had a staying power with me, because I

wrote them many, many years ago, and maybe not in that form. They were

written more in a long song form where there was lots of words and

there was lots of this and lots of that. I kept thinking, you know the

things I like about this song is this line, that line, and that line,

and I always highlighted them and thought the rest was just really

waffle. And then the other thing happened and I'd stop thinking about

it as that song, and in fact that didn't have the same melody or

structure or anything like that, so there was just some lyrics lying

there. Then I had this (sings opening riff)-I had that maybe four

years ago or something, and I must have played it to Yes once or twice

and said what do you think, and they passed on it basically, so I had

this kind of steel guitar group. It was actually a guitar and steel

playing the same things, and I thought it was sort of a "Going for the

One" sort of sound, it had a sort of rocky feel and all that,

but I coupled it with this slightly more melodic piece that I play on

the old GTR sort of synth-the one we used on there called the GR-700.

I like that sound because it's a nice retro sound, and it's one of the

settings that I like.

It seemed to be a great vehicle for the band, i.e. that Dylan

gets some drum shots at the end, and it had this structure where it

kind of went somewhere and rocked out for a little bit, and nothing

much really happens, but everybody just kind of cooked, and in a way,

that's why it kind of assimilated as the first track because, (sings)

"This has always been our home... " had a sort of slightly pleasant tone

to it, and yet there was something aggressive under the feeling of

"Cobblestones"-that there was a better place. It starts with one two-minute segment of an afternoon I recorded

in the garden at Langley, and surprisingly there's so much going on.

It's ridiculous. I mean, there's all those creatures and birds and

woodpeckers, and they're all happening at once, and there's bees

flying by the microphone, if you listen on headphones, it actually

starts with a bee going bzzzzzz, and it's all natural. There's no

gimmicks; you know I didn't pan anything. I didn't add any reverb.

There's nothing there but just the sounds, and my idea there is to

just go from this tranquil place into a song that kind of couples the

journey between those two places like the city/country dilemma, that I

guess I have in my life where the city's energy fueled me for so many

years, but now it seems the country's energy fuels me for another 25

years, so I guess that's strange. Sometimes I look into it; I question

it, but I enjoy it. Those words "I've seen the innocence of dawn," I

know you asked me earlier, "Is that what you say," and I guess that's

almost a reference to psychedelic eras when I first went to the

country and felt I don't own the country, but I belonged in the country

or I related to the country, and I did see that innocence of dawn. I

saw things I'd passed by before. I'd not noticed them; I wasn't

focused on what was going on. It's very fulfilling when tracks like

that and particularly "The Chariot of Gold", which is a song I've also

been kicking around for three or four years that I'd always believed

in. I wanted to get it off the ground.

MOT: How about

"Bee Stings"?

SH: Well, "Bee Stings" and "Smoke Silver"

are the tracks that really helped to explain how I made the album,

because I was working with Roland, and I was listening to what was

coming out of my VG-88 and thinking some of this is good and

I don't need all of those patches, but that's a good patch. I had sat

down and recorded a couple of tracks just using the system, which is

basically all that's on those tracks is me playing different, very

selective settings of the VG-88, and I mocked it up with a drum

machine and things like that, and then it

was after I gave it to Roland and they put it on their website and

you could listen to this like mini-version of those songs for three months or something, and then that's when I suddenly

thought, "You know what, I think I should start an album." Those two

tracks, they're kind of different. So I felt that although there was a

simple groove in "Bee Stings" (sings part of song), sort of this

almost Rolling Stone-ish sort of simplicity, I just wanted to go

there, and that's where I want to be. It's the kind of place I want to

be, and too much airy-fairing around kind of gets me restless for some

head-down playing, so there's a bit more of that idea that I've got

this really high theme that's only really a few notes (sings part of

song), but that's the kind of wailing kind of experience to play; and

that's what I'm discovering the guitar sounds in there, in the VG-88,

and having a structure that I'm more or less invented in the best way,

it's always good sometimes to invent a structure you really like, and

then just work out what you're going to play on top, and that's how I

did "Bee Stings".

I worked very hard on the structure when I was creating it, and all I

was going on was an instinct that, well, if I got this structure like

it really went here-that's just the bass and drums, so I was

writing the bass and drum parts on those two songs for long time, so

that I could actually imagine it was a great platform for me just to

go crazy. I didn't even know what I was going to play, so those tracks

were improvised in another sort of rotation of what improvisation is.

When you've got a structure that's solid obviously you can have

so much fun then, because you can play something and go, "No, one

back, no that's not good. Hmm, that's good; hmm I should play that

here," and start kind of constructing your music, but there's not many

tracks on the album like that. So those two tracks were done like

that, and they started me thinking I've got an album if I look for

material that somehow is like this, sort of a bit progressive but

mainly rock, and so therefore maybe I'll pull out "Westwinds", which

is the next track you're going to ask about, and "Westwinds" and

"Pacific Haze" were just like dying to go somewhere. I just wanted

these tracks to be out to show what I'd been up to, and I didn't want

them to sit there any longer.

I'd spoke about "Westwinds" a bit, but before Andrew got involved, I

constructed it more or less as you hear it, with the keyboards. Adding

the bass was fantastic and Dylan playing the drums... I mean, I conceived that and invented it around

the structures that I had.

MOT: I really heard a Chet influence on your playing there.

SH: Yeah? The way he jazzes it up a bit

and the way I do, in "Westwinds"?

MOT: Yeah.

SH: Yeah, well, that's great. I guess when

I saw Chet this afternoon on there [TV], especially that very early

stuff when he's playing electric, I'm in heaven. This guy just

indicates the value of having followed him for so many years, because

to see how he did it live is really the most interesting thing.

MOT:

"Where I Belong" has a pretty funky solo. What guitar are

you playing in that one?

SH: Well, there's a Dobro solo, then

there's a Broadcaster I think it is... "Where I Belong" is track 4, isn't it?

MOT: Yeah.

SH: Yeah, it's a Telecaster. Yeah, that

Telecaster really is quite a favorite of mine. It's a kind of song that makes me smile. I like things that give me a twist on

myself. I've been hammering down loads of songs, and I had written

this song a couple of years ago in a whole period I wrote twelve

songs, and I thought, they were all together, and now I've

seen that they're actually a nice bed for me to pull from, so I pulled

one of them out, and it was that song because it was the most an R &

B and country pickin' mixture I had--basically kind of a blues song,

but a bit along the lines, because all blues songs have to start off

with some sort of epitome of sadness in some way, and to say that

you're down on your luck is a classic blues twist, if you like.

I improvised that line one day, (sings) "I've been down on my luck for

a while, hardly able to raise a smile." I thought that's alright; I

like that. So I grew to like it and molded the song really to keep it

pretty simple, and not to give away what it's really about. It's one of those songs that I think hides a little of what

it's intended to mean, but more in playfulness; it's not funny just to

go out and say what you mean. In fact, there used to be a bit where

I went "Dreaming... " and I said a little bit more, and that's where I

went "No, I mustn't say that." What happens with the "dreaming" section

is that the first time it's just (sings) "Dreaming, it could be like

this", and the next time it's (sings) "Dreaming, da da da... ", you get

another line, so I kind of build the place for that part of the song

so it grows, because too much of that at the beginning seemed to give

it all away. But the way the guitar happens with that, what I think of

is sort of Albert Lee-ish-he's one of my big idols, I've talked

about him a lot recently, because he really did affect me. It's not

that I can hear enough of this guy or I've got like ten CDs with him

on; he's actually under-released or something-brilliant, but his

influence has stayed with me right from the word go... it's a bit like

the tune on QUANTUM GUITAR, I think it's called "Country Viper" (sings

opening riff of the song). That's me; I'm a sort of dichotomy of my

own tastes. The taste I have for music can go in like the poles of the

Earth; I can go south and go into, say country music and really go

there big time and believe that I've really got to stop all this

messing around with Yes (laughs), I've got to go and play some really

good country, so I get these pulls towards different polarities in

music, and I love it. I just love being tempted, or allowing myself to

feel that I'm going to do things, and they're usually very good

stepping stones for things that I do in the future, otherwise what

would I do next as a solo input guy, but I also want to create some

continuity. I'm not going to be seen with the cowboy hat on one minute

and then a Spanish guitar the next. I think there's a way of doing

this gracefully, where my projects keep having central themes, but

also like merge left and right as well.

MOT:

"Whiskey Hill": that is a really rollicking tune, rocks

kind of like "Going for the One" does.

SH: It's all pulsed by one guitar that was

played really when I was very, very excited by what I hear. You see, I

think I respond to the sound. If I'm making a good sound, I'll play

loads of good stuff... so I'm standing

in the studio going (sings part of a guitar track), just on one guitar

with all these delays on it (sings more) (laughs), thinking "Wow!"

(sings more), and what's keeping me in time of course is all these

delays, I'm playing more or less in the tempo of the delays, so it

just started life as a really crazy piece of guitar that just stood on

its own, and then I invented the idea that to take it off the ground,

to introduce it as a guitar, and the band then treat it almost like a

Chuck Berry song. One of the guitars I really like on it is a really

awful sounding guitar. I mean I try and make beautiful sounds all the

time on the guitar, but every now and again you just got to have

something that's really nasty (laughs), and there's a wonderful, nasty

sound on there that goes (mimics part of guitar sound). It's kind of

grinding away in the back, and I think that's what rock music is

partly fueled by is distortion, and there's none on SKYLINE, and

there's none on NATURAL TIMBRE, but there's some distortion on this

record (laughs), and I like those bits that I can dovetail. What I've

been doing for years is sort of like dovetailing guitar playing. I've

got a guitar that I like, and then I see a space for something else,

and I create a new line, I can then see that as a part. So in a way

it's strangely orchestral, a piece like "Whiskey Hill". There's a sort

of orchestral spacing of the way things happen in it, but the

orchestra's made up of (sings nasty guitar part) on a Dobro guitar,

and that Fender Strat that's tuned to A, so you get all these

different kinds of intonation-- SH: It's all pulsed by one guitar that was

played really when I was very, very excited by what I hear. You see, I

think I respond to the sound. If I'm making a good sound, I'll play

loads of good stuff... so I'm standing

in the studio going (sings part of a guitar track), just on one guitar

with all these delays on it (sings more) (laughs), thinking "Wow!"

(sings more), and what's keeping me in time of course is all these

delays, I'm playing more or less in the tempo of the delays, so it

just started life as a really crazy piece of guitar that just stood on

its own, and then I invented the idea that to take it off the ground,

to introduce it as a guitar, and the band then treat it almost like a

Chuck Berry song. One of the guitars I really like on it is a really

awful sounding guitar. I mean I try and make beautiful sounds all the

time on the guitar, but every now and again you just got to have

something that's really nasty (laughs), and there's a wonderful, nasty

sound on there that goes (mimics part of guitar sound). It's kind of

grinding away in the back, and I think that's what rock music is

partly fueled by is distortion, and there's none on SKYLINE, and

there's none on NATURAL TIMBRE, but there's some distortion on this

record (laughs), and I like those bits that I can dovetail. What I've

been doing for years is sort of like dovetailing guitar playing. I've

got a guitar that I like, and then I see a space for something else,

and I create a new line, I can then see that as a part. So in a way

it's strangely orchestral, a piece like "Whiskey Hill". There's a sort

of orchestral spacing of the way things happen in it, but the

orchestra's made up of (sings nasty guitar part) on a Dobro guitar,

and that Fender Strat that's tuned to A, so you get all these

different kinds of intonation--

MOT: "Tuned to A"?

SH: I think that is... let me just check if

that's right. We're talking about "Whiskey Hill", right?

MOT: Yeah, yes we are.

SH: eah,

that's right. What I do is tune the whole guitar, instead of E, it's A

below it, so it's actually a long way down. All the strings are all

flopping about all over the place...

MOT: You mean the high and low strings are As?

SH: Yeah, imagine if you had a tremolo arm

on that could take your E chord to an A chord below it; that's kind of

where the guitar is pitched, so the guitar that starts--

MOT: So that's the main guitar the part that goes (sings main

solo guitar line

of song).

SH: I think the one that

starts it (sings another part)-it's like a country pickin' guitar

(sings small part)-that keeps coming up in the mix every time it's

kind of being featured, and then you get (sings descending

line)-that's the Les Paul Custom doing the kind of interfering guitar

that comes in. Yeah, it's interesting what music allows. Sometimes

what you don't know is best, but that line, the one I'm thinking of

anyway in "Whiskey Hill" comes in about after about 40 seconds, when

the tune's picked up and this quite raunchy sort of heavy guitar comes

in, and actually as I played what I played on there, I noticed that I

kind of expanded the scale a little bit in a particular way. I think,

"Hang on a sec, I'm in that key," and it worked beautifully, you know

what I mean, and it was what I didn't know about that was good, not

what I knew, and that's obviously noteworthy in a strange sort of way.

MOT:

"Chariot of Gold", that's one song that I thought had a

real QUANTUM type of feel. I was wondering if it was written around

that time.

SH: Yeah, I think it was QUANTUM... that

was '96... yeah it was about that time.

It was a troubled piece because what I

said in the song was hard work for me to keep doing it. So I rewrote

it, but I just rewrote it in an even more hard work way (laughs). It

was a very tentatively dynamic song, where it was using images like

"The Chariot of Gold". You didn't really know what "The Chariot of

Gold" was in the song, but you could guess if you like, and this had

actually got on my nerves, so I took all of the melodies that I've got

going as a vocalist, which was one of them in the middle of the song. I just played it on electric mandolins, and I thought

that's what I'm doing; that's what I do sometimes-take the song, throw

the song out and take it as a guitar, and it's great because I can

take that melody and it's almost like I'm singing really, but I'm not.

I'm playing it on the guitar, and it really is good fun. But what's

maybe better in the end to say about it is that because it was a song

that had all this time and thought and different perversions and

different arrangements, different drum kits, endless attempts at doing

it on 24-track with somebody else... when it just comes out and it's all

that clean, it all got cleaned up and it's got the saxophones on it

that I wanted, and Gilad takes that solo at the end that really is

quite steaming so for me; I pulled it off. It's one of those long haul

numbers-really nice. I mean, some numbers that we're going to talk

about some that just happened out of thin air, and then other numbers,

you know it's a balance that take a lot of work, yeah.

"Tremolando", do you have any questions on it?

MOT: Yeah, actually I do. It's funny, because throughout your

career you have pieces of a different facet--"Clap" was your solo

ragtime piece, "Mood for a Day" is your big solo classical piece.

"Sketches of the Sun" is like this electric 16-string piece, or

"Masquerade" is the acoustic 12-string piece, and now you've got "Tremolando",

and I kind of felt that was in that same vein. This is your big

tremolo song (laughs).

SH: Yeah, yeah, right. I guess on Chet Aktins'

FINGER STYLE GUITAR,

there's a piece, I think it's by Scalatti, and there's a little minuet

sort of piece that he does, I think it's called "Minuet in A". I might

have some of the titles wrong there, but it's a very classical piece

and Chet played it. It didn't have tremolo, but it was in A. And how I

recorded a few tracks was that in my studio, I'd have all my effects

rack wired into my studio, so I'm through like any number of things

that I want to be at the same time. The only down side to that is

sometimes, and "Tremolando" is actually an example, I don't actually

know what gadget I used to do the tremolo, but it may be that Daddy-O

brought out a little tremolo that I really liked. It's got very

intense tremolo; it's got two tremolos. One is a on and off, totally

on and off, and the other one is a really good sweeping, slow and then

fast; it may be that pedal, I couldn't remember when I did this, I

literally could not remember.

So basically I was improvising, I was just having a nice time playing,

but what I tend to do when I'm doing that isn't just play endlessly, I

kind of play something, and then I'd think, "Oh, well look... hang on,

this is going somewhere," so I restart it, but the DAT is still running, so

there's a DAT recording the stereo send of any amount of effects,

reverbs I want or none of them, just a pure guitar and a foot pedal.

But it goes down onto tape, so it isn't a multi-track, it's so you can

have solo pieces. So that's really how that came about. I played that

tune, and I was just really impressed that I did it, but I'm just

thinking that it might actually be that I recorded that piece as well

in Vancouver, but I think it was done in Langley. What number track is

it?

MOT: Seven.

SH: Yeah, I think it's the Korg A3 SH

setting; there is a tremolo on there, and I've got there the

Steinberger six-string... so melodically that's just perfect because

there's not much to it. It's funny how people work so hard to work up

tunes with endless bits, and obviously it's a short piece, but at that

tempo with that tremolo... as I was about to say when you first started

talking about it, in the early days it was about the only effect

anybody had-tremolo (laughs). It was like, "Have you got tremolo? Yeah.

Well thank God for that," and you used it occasionally, and Chet used

it brilliantly on a tune called "Take a Message to Mary" and other

times. It comes back with regularity. Back in those days, I think

Duane Eddy always had tremolo on his guitar. So it was seen almost as

part of the sound the guitar made, but of course it actually came from

xylophone technology, didn't it? Vibraphones.

MOT: Yeah, that makes sense.

SH: And some players liked it, and some

players never used it at all... I think Lionel Hampton, or one of them,

never used it at all. Who's the guy that started out with Hank

Garland... anyway, it's just one of those things that has a moment in

time when you've got all the focus. What's nice about guitar solo,

even in the electric world is the nothingness of your space, you have

nothing. You're naked, if you like, and it's quite interesting how

that feels; like when I do "To Be Over" on stage at the moment.

Sometimes that's quite a risk for me, because particularly when we

went to Singapore, I seriously thought about doing two familiar tunes,

but I thought "No, I'll play this."

But it certainly puts me somewhere. You know, there isn't just

strumming along, it puts me in danger (laughs) of hope of keeping that

together and presenting it as an entire piece. But always solos demand

different technique, and in a way that playing "Tremolando" is a

different sort of technique. I guess what helped me was being

interested, generally interested in chords, thinking that they were a

sort of mystery, like a puzzle, like having a crossword... something you

have to kind of complete to find out how you do or make all those

things possible. Chords constantly help me to play as a solo

guitarist, even more than what I do in Yes, which is partly chords and

partly single notes, but like I was telling you about Chet had to

arrange how he could go from solo playing and then have backing and

then that was cleverly done. So "Tremolando's" got quite a confident

footing, because it isn't really going a long way, but it goes a long

way without doing much, which is nice.

MOT: Yeah, it is very effective.

"Pacific Haze"... a rare

foray into jazz.

SH: Yeah, this really is a big track where

it grows, it develops, it kind of winds its way through a lot of

things, but oddly enough there is some very strong structure about

it... that track in particular, as I said was done in an unusual way... all

I know is that when you listen to the track, that's the track that

people take to in a different sort of way, because it isn't very usual

for me to move so far into that, to take a big chunk of work and say

let's have the freedom that I want in this piece but have the

structure too-the brass ensemble.

MOT: One thing that I was wondering was how you communicated

the arrangements--"Pacific Haze" is one Andrew Jackman did, correct?

SH: Yeah.

MOT: Did he do the arrangements for the horns--

SH: He had completely free arrangements,

yeah.

MOT: --or did you have any input there?

SH: No, I didn't. I mean, I told him where

I wanted it definitely to be... certain places I said to him, "You got to

be doing something here; at three minutes fifteen I want you to come

in here." I might indicate whether I was like trying to raise the

crescendo or whether I wanted something very smooth; but I gave him

very, very little to go on, mainly just timings of areas where he

definitely ought to be doing something. He didn't have to do anything

everywhere, so he dreamed up his own way of introducing it gradually.

He did that completely on his own, and I didn't even hear it before we

recorded it. I trusted him completely to come up with something, and I

wanted an input, you know I wanted somebody to come up with something,

and I knew he could, and so that's the first time I heard it in the

studio, so that was terrific. I already had Gilad playing on the end,

but I didn't have him on the same tape, so the first time I had got to

Curtis's [engineeer Curtis Schwartz] after that session and put "Pacific Haze"--put all the tapes

together-all Pro Tool files together, and put them with our track and

then I said, "Let's put Gilad off on the end as well" (laughs), so the

track is going to end, and suddenly Gilad comes in, but a little

(laughs) on the top of the brass, and it's just fantastic. I played

that to Andrew, and he thought it was going to work great with his

arrangements. SH: No, I didn't. I mean, I told him where

I wanted it definitely to be... certain places I said to him, "You got to

be doing something here; at three minutes fifteen I want you to come

in here." I might indicate whether I was like trying to raise the

crescendo or whether I wanted something very smooth; but I gave him

very, very little to go on, mainly just timings of areas where he

definitely ought to be doing something. He didn't have to do anything

everywhere, so he dreamed up his own way of introducing it gradually.

He did that completely on his own, and I didn't even hear it before we

recorded it. I trusted him completely to come up with something, and I

wanted an input, you know I wanted somebody to come up with something,

and I knew he could, and so that's the first time I heard it in the

studio, so that was terrific. I already had Gilad playing on the end,

but I didn't have him on the same tape, so the first time I had got to

Curtis's [engineeer Curtis Schwartz] after that session and put "Pacific Haze"--put all the tapes

together-all Pro Tool files together, and put them with our track and

then I said, "Let's put Gilad off on the end as well" (laughs), so the

track is going to end, and suddenly Gilad comes in, but a little

(laughs) on the top of the brass, and it's just fantastic. I played

that to Andrew, and he thought it was going to work great with his

arrangements.

MOT: That was particularly enchanting, because we really have

a chance to hear you play jazz of that kind. You've alluded to jazz

with Yes...

SH: Yes, It's coming in, slipping in

discreetly I hope into a sort of gaining acceptance through not being

the sort of main body of the music, but in some way it gives me a

chance to show why I've been playing like that, because I also

conceived of writing tunes that are like that... "Sweet Thunder" was one

of my first pieces that was actually, very obviously, in a jazz

direction, and that's a piece that I like a lot. I really want to play

that, because I had a stab at it with PULLING STRINGS, which was quite

fun, and I feel that that piece is a really jumping piece; by

rearranging it, I could use a couple of ideas again in that, and it

will really jump about.

Now, I played bass on that because when I was doing the bass sessions

with Derek, he sat in everything absolutely great, and we came to

"Pacific Haze" and I said, "Well, have you learned this one?," and he

said, "Well, I didn't know where to start really," because the bass

just is flying about all over the place. So I said "Well, let's look

at it." At that time, Andrew was the only person who could have maybe

given me a chord structure to what I had written... [or] maybe I had one,

but I didn't know where it was, but the chord structure changes a

great deal. There's three bars of this chord and four bars of that,

but somehow it seems to flow, and so he said to me "Well, give me a

couple of runs at it," and as soon as he started you could kind of

sense that the bass had become really locked in. So we went with my

bass, which I was quite happy to because I think it shows a little of

my previous solo work where I get my guitars to sort of, I hope,

interact properly. Every note the bass played was designed to be with

that guitar, and I designed it, and in a way, Derek didn't want to

redesign that one (laughs), because it was complex.

MOT: Yeah, it worked extremely well.

"Load Off My Mind" I saw

as having a very Dylanish chorus.

SH: Oh yeah... "Come and take this load off

my mind" (sings). Yeah, I think I was lucky to find that expression,

because it was what I'd wanted; it doesn't quite tell you what the

load is, but it's a load, and I think that's a good thing to go with,

and the song is based on any kind of basic rock song, I mean not a lot

happens.

MOT: It almost had like a feverish electric guitar.

SH: Well, I play a lot of tribute to James

Burton on that one, I mean, that's my kind of James Burton parts that

in a way became adopted by so many guitarists in my era. Everybody

knew how to play James Burton's lines, like they knew how to play Hank

Marvin, and other people wanted to learn how to play Chet Atkins.

The fact is that that song is something I quite wanted to sing, and

that's why it's there, it's because it was kind of mean enough, it's

kind of meaty enough to be rock piece of material, and as you said,

that it's slightly Dylanish line about "Load Off My Mind", but yeah,

I'm pleased with that. I'm pleased that settled in to my repertoire.

MOT: "Hecla Lava"

was recorded during the time of THE LADDER?

SH: Yeah, I hadn't given any actual

notification of that on the album exactly where some of these things

were recorded; most of them were recorded in my studio, as everything

we have been talking about was, except the brass. But basically "Hecla

Lava" was recorded directly from a GP 100. That's what it says on my

CD listing, and how I did it was to play the 175 into the GP 100, it

came out two Advent speakers, and I had a stereo mic recording on a

mini-disc. Basically I got a lot of source material like this, by

inventing pieces on these sounds as I worked though the process of

noting which ones I liked. So those pieces became almost a new solo

venture for me to play on electric sounds and move about electric

guitar if you like, with weird and wonderful sounds.

There's only two like this on the album, "Hecla Lava" and the other

one's called "Sand Devil", and they're both recorded in Vancouver at

the time by myself in my hotel, it was kind of an apartment we had. I

just kept the mini-disc and then I took it on to Pro Tools, and then I

coupled a few of these together. Usually the ones that were next to

each other, I'd slightly edit the end of one or change the beginning

of the second one, so I'd mold it into a little suite if you like of

textural sounds that is more about the sound really than the notes.

It's a kind of a guitar soup of a solo, and I like to do different

things; it keeps me thinking.

MOT: Playing in terms of keeping time with what's happening

with the echo of what you just played.

SH: Yes, that's part of it. That's always

been a wonderful place, in fact I'll credit Roger Dean a little bit

for making me realize that many, many years ago, most probably in the

'70s--or it could have been in Asia days, but he came into a rehearsal

room and I was playing on my own, and I didn't know he was there, and

so I just carried on for a while (laughs), so when I eventually

stopped, I said, "Oh, hello Roger, how are you? How long you've been

there?" He said, "I've been here for about 10 minutes," (laughs) I

said, "Oh God, I didn't see you." And he said, "That was great," and

it was a bit like this stuff; it would be just kind of standing there

going (mimics guitar sounds), and it's amazing that I can play for so

long sometimes.

You know,

[yesterday] we rehearsed "Close to the

Edge" and "Magnification", then I played about 20 minutes on the

acoustic guitar, and then I checked all my guitars again, and then I

played that huge set with Yes last night, and that's a lot of playing

in one day-hours, absolutely hours... three, four hours of playing. I can

get into playing quite a lot, so if I'm recording things, then I get a

great backlog of quite interesting guitar recordings, like "Hecla

Lava", that I can sort of balance this record with, because I didn't

see it as a straight rock record, you know what I mean. I saw it to

have adventurism; it has adventurism with the jazz tracks, and it had

adventurism with these solo versions.

MOT:

"Smoke Silver"...

SH: Yeah, I like this. This is one of my

favorite tracks. I don't know why, but there's something really

straight ahead about it... I like having bass riffs like that (sings

opening bass line)-very kind of snappy, so I guess like I said with

"Bee Stings", this is the coupling track where I use VG-88 guitars

exclusively, and I didn't write in the usual constructional way. I

created a structure, and then I invented the guitar lines that go on

it on the tune, so that's just another way of writing, which I think I

like, I like to keep writing in different sorts of ways, but... yeah,

that one molds quite a lot of the guitars I like from VG-88, and I

list the settings on there that I use.

Yeah, just fun; I mean that's what I had, you see, "Bee Stings" and

"Smoke Silver" were just fun to do, because I didn't really stop to

think what I was doing. I was just having a ball doing this crazy

stuff you know, and I try to carry that through in the way I thought

about the album, that is wasn't all going to be beautifully correct.

Some things would be a little bit strange here and there, and that is

a kind of product, if you like, of the kicks of rock.

MOT: Keep the element of spontaneity.

SH: Yeah, yeah.

MOT:

"Inside Out Muse", that's one of the longer songs on the

album. That's a very evocative blues song, your playing is very

evocative.

SH: Well, I've never released a 12-bar

blues, and this one's very similar to a 12-bar blues, and I thought if

I'd do something like this, I want to cover some of the ground that I

like in this style, so what happens is the lead guitar improvising

starts quite clean, introduces a sort of mood, but then kind of

discreetly changes sound and becomes a little bit more angry sounding;

and because of that, I can only think that the '60s and early '70s

were a very exciting time, when I wasn't terribly aware of how well I

was playing, and it was rather nice. And some of the effect of that is

that I have great memories of moments in playing in the '60s and early

'70s, and right before Tomorrow, before the In Crowd, the Syndicats

were a blues group, and of course I used to play a lot like this in

those days. I used to combine the blues approach with jazzy bits that

I got from records or Albert Lee or somebody, that I thought I could

pick up some phrases.

But I was really pleased to see Albert, because he uses that sort of

double-stomping thing that I was using before I saw it, and the

two-string idea--but he was using it in a rock fashion like I do, and

although I don't really do any of that on that, there's a tendency for

me to go just across the 12-bar style, almost as if I'm flying a

Concorde for the first time. It's like "Hey, somebody's letting me do

this." It's kind of myself really, but I almost felt like on this

record I had that much to say in different ways that related to where

I belong, that related to "Load Off My Mind", a kind of the rock-blues

kind of side, so to leave the album without sort of making a statement

in the blues thing I thought would be a shame. And so it stretches

out, and it kind of slowly builds and then Gilad comes in, playing of

all things a clarinet, which was just the right for the moment.

MOT: Oh yeah, very beautiful solo.

SH: Yeah. But we have support saxophone

from him as well, which are playing a slightly, dare I say, a "Night

Train" kind of feel about it, which I like. Gilad hasn't been

mentioned enough, because it's always great when you meet a musician

who on his own instrument far exceeds what you can do on your own

instrument... and we start recording, and we're looking at this, and the

first thing works, yeah, this is good. I start with some clear

recording, something like "Chariot of Gold" where I knew exactly I had

(sings riff from song) on some synth saxes, so he replayed all that

stuff and got it all shaping up great. But through the sessions I had

with him, when we got to "Inside Out Muse", he just said, "I don't

think sax is going to work. Let me try this," and he got it out, and I

said "What are you playing?," because he was in my other room, and I

couldn't see him at the time, and he said "Oh, I'm playing the

clarinet," and the sound was perfect, so it was a nice marriage of

that.

Virgil also plays really nice... he starts the track with a little pling

of a chord that shows his kind of presence, where he's a spacey kind

of electric piano in this one, and that's nice.

MOT: And of course Dylan's jazz drumming elevates it to a

whole other level.

SH: It does! His work on this album is so

good.

MOT: It could have been a stock drum beat, and it would have

been good, but what he does on this song ...

SH: Well, Dylan called me and said, "Well,

I've listened to it. I think this is the best think you've ever done,

but I think it's also the best thing I've ever done," and I was really

pleased to hear him say that. He likes the opportunities we've found

here, and certainly on that track, you know on the multi-track, we

were faced with some options, we sort of thought we had problems but

they didn't exist because when we put it all together, they went away.

It's just like suddenly the whole track kind of went... "Oh, well now we

sorted that bit out and that bit, now... " So we had just a few little

areas to correct, where we felt the guitar wasn't strictly in time

enough here and there, so we corrected those bits and we said, "Well

there aren't any other problems." But the way that Derek plays bass on

this, he's at home with that kind of approach, so everybody was quite

happy, had fun with that, but it's an easy-going thing. I'm glad I've

got a blues that has a style that I like. [Seeing what's next on the

list he sings the opening guitar of

"Rising Sun".] SH: Well, Dylan called me and said, "Well,

I've listened to it. I think this is the best think you've ever done,

but I think it's also the best thing I've ever done," and I was really

pleased to hear him say that. He likes the opportunities we've found

here, and certainly on that track, you know on the multi-track, we

were faced with some options, we sort of thought we had problems but

they didn't exist because when we put it all together, they went away.

It's just like suddenly the whole track kind of went... "Oh, well now we

sorted that bit out and that bit, now... " So we had just a few little

areas to correct, where we felt the guitar wasn't strictly in time

enough here and there, so we corrected those bits and we said, "Well

there aren't any other problems." But the way that Derek plays bass on

this, he's at home with that kind of approach, so everybody was quite

happy, had fun with that, but it's an easy-going thing. I'm glad I've

got a blues that has a style that I like. [Seeing what's next on the

list he sings the opening guitar of

"Rising Sun".]

MOT: Canned Heat meets Steve Howe...

SH: Oh, you see it

like Canned Heat? I see a bit like "Whiskey Hill", a kind

of continuation. It's kind of very, very straight ahead. We're not being

too unhappy with just being straight ahead.

MOT: It's like a boogie...

SH: There's a boogie. It's a sort of

holding back tempo boogie until the saxes got to go to double time

(sings sax part), and I think then there's plenty of chaos there when

the steel guitar takes a break and kind of bends the notes around

(sings some more), and then we're off into more saxes. Steels and

rockin' guitar-it's a really straight ahead, down-home sort of track,

boogie.

Well,

"Sand Devil", the other experience solo track, recorded in my

Vancouver place, and basically it's the same agenda if you like,

playing the guitar but we're somewhere else in time, in sound; we've

got a slightly different working of it. Titling instrumental music's

really quite a lot of fun, and I get a chance to use words and

connections with things, and one of my favorites is on SKYLINE, "When

Georgia Moves To Bristol", which we found a really beautiful city, and

she started taking us places in Bristol. One of them was a camera obscura, and I didn't really know that expression, and I didn't even

know what it was, and it was this building you'd walk in, and when you

look down, you see the reflection of everything around you, 360°. I

was thinking about that, and it might seem a bit obscure to suddenly

call it a track, but ok, well I was doing SKYLINE, and Paul [Sutin],

unless he had an idea, would always leave the titling in to me, and if

I had an idea and he liked it, it was bought. He would say, "That's

great. I like that." So we're doing those tracks, finishing up a

couple of tracks within one day, it had some title like Number 7 or

something (laughs), so I kind of said, "Well, I've got an idea. I

think I'm going to call this "Camera Obscura." It is fun.

I was talking about "Sand Devil" because there's things that stand

out. I take pictures, as you know, and I might have a lot of sand

devil pictures somewhere, and those kind of weird phenomena things

going on around that you don't think of are just nice. Obviously a bee

sting isn't very nice, but that's because it tied in with Remedy

beautifully, the Bee String... maybe we don't need to go there, but just

talking about the Remedy side of the album in a way that we haven't

really looked at all, is the suggestion that part of this has (laughs)

any literal sense at all in the fact of having a title like "Sand

Devil", but certainly mentioning "Hecla Lava", which is a homeopathic

remedy, and the first one I ever took, and it was obviously the first

one that worked as well, and it was a remedy, but it comes from

organic dusts. We think about that quite a bit these days. We're in

Hawaii at the moment (laughs). But anyway I like pulling things in and

recording a piece of music. "Joe Had Coffee" might be alright if you

relate to that, but my titles kind of relate to things that I like,

and

"The Longing", the next track, is really one of the most

surprising tracks I discovered in my recordings ever, because I'd

forgot about this track for almost probably 10 years.

MOT: Oh really?

SH: Yeah, I'd hardly know what I did, why

I did it, where I was... I was at Langley, but where I was in my mind,

and why I was making these unusual sounds.

MOT: You know, it's very dramatic.

SH: Yeah, it reminds me of on QUANTUM

GUITAR, there's a piece called "The Great Siege". So titles are

interesting sometimes, but "The Longing" is very electronic, very sort

of '80s Prophets sounding, although it's guitar-driven, using the synth. Now I did have... a Roland keyboard, that I don't know if any

other keyboards sounded like this one. It was only a silly one with

speakers in it, but it had some brilliant sounds in it. I know I've

got the number somewhere; I should get another one. But I got a

feeling that some of it's driven by that, because it had some

sequencer in it, and I like messing around with that stuff.

But the whole placing of the music you is somewhat of a mystery to me,

and for that reason I like it lot. It was always called "The Longing".

I found a tape from like 10 years back-"The Longing". The title had

been on there, because it emphasizes, in my mind, that mood when you

long for things that you don't have, and so that track just made me

happy when I found that some time back and realizing that it was

available, that I had a track like that that fitted with "Sand Devil"

and "Hecla Lava".

MOT: So, this track that's on the album, is it that the original

version? Or did you rerecord it, or take that and extend it?

SH: Actually what I did with it was we

added drums to it. That's what we did; all those basses are actually synth basses, and we just added Dylan on drums. It's all we did; I

mean we remixed it. We took it; we got back to the master and put it

onto Pro Tools, and then added drums.

MOT: And then you end with

"A Drop In The Ocean", and for some

reason that just the feel and the tone reminds me of "The Last Waltz".

It had that kind of liltingness to it.

SH: Yeah, when I found all these parts that I'd recorded, they were all

sitting there, and after I had played virtually what you hear there

over slightly longer time with a few gaps or a few changes, then I

played (sings opening of "Swanee River") and it was almost as if I had

that in my mind, you can almost sing "Swanee River" to it. It would be

a counter melody. But I'm going (sings main melody), and I dearly

love that. When I go out with Yes next time, I hope to be playing

"Tremolando" and "A Drop In The Ocean", and really like making that a

statement, because I think it's very interesting how you can get such

a mood swing, because that is a pretty big mood, "A Drop In The

Ocean". It's a nice place to be. It's full of anticipation. You may

never really get there, but the anticipation is there... I guess what Yes

used to do in the really early days was spot these. Jon used to spot

them and say "Now, that's a good one. Let's have that one (laughs),

let's have that with that song. What song will that go in? Or have you

got something that will go with this?" and the whole exchange of ideas

was done on a pretty special level.

Yeah, "A Drop In the Ocean" is really quite pretty. I guess after some

of the excitement and challenging moments, I felt it was quite nice to

leave the record on a sort of pleasant note really, and hopefully feel

like it's a conclusion to something, because I think it's like the

finale to it.

MOT: It definitely seems like an appropriate closure to the

album.

SH: Well, that's another important thing;

it can be a nightmare, a somewhat almost self-induced almost nightmare

about the running order, and I think I met [with] you when I was

having a nightmare about [the running order for] SKYLINE. Well, what

happens is some records really get to a scary point where it seems

very dramatic about where different tracks sit, and at the end of the

day of course nobody knows you go through that, and it's like it's the

final chance to say "Hang on a second. That doesn't go well from this,

or it's in the same key." Getting the keys to be different and getting

the whole mood of something kind of coming in and then following well,

and then showing some development in the music, that 1%; and sort of

doing all the things like assuring and then kind of challenging and

then satisfying, bringing it all around I guess.

It's quite fun making a record; that's why I mentioned earlier that

the time when you first think, "Oh yeah, I think I've got a record,"

suddenly the tracks get there. I thought that maybe when I

wrote those 12 songs a couple of years ago I had just written my next

record; it's all vocal (laughs), "but maybe I shouldn't do this." So

unfortunately I had other things to do which distracted me from

thinking, "Hmmm, I should try and take this on," but it would have

been far too much. I also really enjoyed arranging music, and you can

do some of that after you've played it as well, which is really good

fun nowadays...

The things that Eddie [Offord] was doing at the beginning of the '70s, people

were doing in the '60s, were doing tape-phasing and stuff like that,

because there wasn't a phaser and cutting tape to make the performance

as good as possible, and inserting bits, changing arrangements, doing

all that stuff. It was just part of the course; you did it because

needed to, but also it was a great learning curve, and so I can enjoy that, as long as there's something doing with the music, you

should know about something about how to do it. But there again you

don't have to know how to operate all this stuff, I mean you don't

have to learn that. You can just have the ideas, and that's the other

ingredient to the equipment and the person who can operate it is

somebody with an idea. I know that I always relieve people... well, I've

done it to Curtis often when we sat like this talking at the studio,

and I've said, "Well you know that... I've got these tapes here, and I'm

doing that... " and I've described a little, and he sits there thinking,

"Oh yeah, ok, so you're going to do that. You want a copy of that onto

here? You've got to expand that, ok," and he kind of goes "Well, I

hope you know what you want. If you know what you want, we'll be

alright, because it's the right thing." So he would say, "Oh yeah,

well that's fine now, because you knew what you wanted." But I don't

touch that complexity of it, because I'd be so slow. I'd never get

anything done, so expertise is great.

I'd mentioned Curtis before; we do more than it looks like together

really on the record, and he deserves all the thanks he can get. But

he's very modest about his involvement, and he's very undemanding, if

I mentioned credits, it's, "I don't mind, whatever you think, fine." I

don't get a letter from his lawyer saying please say Curtis Schwartz,

courtesy of Curtis Schwartz Productions (laughs)... it's all very laid

back, and he's very ambitious and a very talented

engineer/musician/writer/player all around, so when you work with

somebody who's got all those skills as well as engineering skills. I

don't use him as a constant buffer, but when I'm somewhere where I'm

thinking, I'd say to him "Well what would you go with here? Which way

do you like here? Do you prefer it when we do this or do you like it

when this comes hurtling in?" and he'd give me an objective view, and

he's been my mainstay, really engineer, for all this time, since

HOMEBREW I. That was the first project I did with him for general

release.

MOT: The unsung hero...

SH: That's right. I've been talking about

backroom guitarists, like we talked about James Burton, and because I did an

interview in Singapore it was about guitarists and are they as good.

They said, "Are the superstar guitars really as good, and are there

other people that nobody's ever heard of?" I said "Yeah, there are.

There's a lot of people you've never heard of who are actually

brilliant, and they didn't pull their careers together. They didn't

have a break, maybe didn't write songs or they didn't get their foot

in the door somewhere to be more than they are," but the other thing

is they might be quite satisfied. They've had a real life. Maybe they

live somewhere, and they've got a real, normal life.

See, to be a musician, you have to sacrifice normality. You have to

become an oddity in the society world, and any neighbor of yours will

think you're weird, you know what I mean, just because of what a

musician does. He goes off; he comes back in the middle of the night,

unloads his vehicle at 3 in the morning. There is always coming and

going, and when he shows up, there is all this paraphernalia, and then

he's gone again, and then there's a black limo outside, you know what

I mean? How do you do that without anybody knowing? You can't, so

people around you know you do all this stuff, and your family gets

kind of, "Where's dad today? Oh, he's in Singapore. Oh I see," so

everything's got a certain kind of place, and it doesn't make it

really any easier. So a musician who decides not to give up his whole

life to his music, but actually remain in the background of public

prestige, if he can earn a good living and stay at home with his

family, I says he's done a very clever thing, because he's done what I

want to do, which is play music all my life, but at the same time, he

could offer his family a normal life. I've not been able to do that.

I've offered them the mad life of being married to a musician (laughs)

and having a touring and recording musician as your dad, and although

it might appear to have lots of perks, it also has a lot of down sides

and a lot of struggles and difficulties and separation and periods of

great difficulty, but it is possible to overcome it. See, to be a musician, you have to sacrifice normality. You have to

become an oddity in the society world, and any neighbor of yours will

think you're weird, you know what I mean, just because of what a

musician does. He goes off; he comes back in the middle of the night,

unloads his vehicle at 3 in the morning. There is always coming and

going, and when he shows up, there is all this paraphernalia, and then

he's gone again, and then there's a black limo outside, you know what

I mean? How do you do that without anybody knowing? You can't, so

people around you know you do all this stuff, and your family gets

kind of, "Where's dad today? Oh, he's in Singapore. Oh I see," so

everything's got a certain kind of place, and it doesn't make it

really any easier. So a musician who decides not to give up his whole

life to his music, but actually remain in the background of public

prestige, if he can earn a good living and stay at home with his

family, I says he's done a very clever thing, because he's done what I

want to do, which is play music all my life, but at the same time, he

could offer his family a normal life. I've not been able to do that.

I've offered them the mad life of being married to a musician (laughs)

and having a touring and recording musician as your dad, and although

it might appear to have lots of perks, it also has a lot of down sides

and a lot of struggles and difficulties and separation and periods of

great difficulty, but it is possible to overcome it.

MOT: You certainly seem to have the advantage of the

semblance, at least, of a stable family, considering your vocation, it

seems like your marriage and your fathership has been resilient to say

the least.

SH: Well yeah, I mean we've done as best

as we can, and some of it's brought terrific results, and...

MOT: Because as you know, others have going that route and

failed miserably.

SH: Yeah.

MOT: It's just a matter of priorities.

SH: Yeah, yeah. Determination, certainly

for me, isn't most of all about money, is that my determination most

of all is about my family and keeping that correct, but of course, we

have a disadvantage by the rules of this game. But there again we try

and utilize as much the control that we do have in our own time to

make our life what we can, and if we choose to do certain things

certain ways, but at least at that time we think it's right, and

that's what a long relationship's really about is change. It's not

about staying the same, but those changes can give clarity to a

relationship, as opposed to having to disassemble it, and then create

weakness for future generations and possibly for yourself as well... we're just thankful for what we've done. Some of it's rewarding, and

some of it continues to be rewarding, so of course they say the family

units not what it was, and certainly in many areas there's a lot of

problems with that, but it also is bad stigma to keep having across

the whole family concept. It's unavoidable because there seems to be

negative pressure to say it's breaking down, and yet for some people

it hasn't. Some people they've got happy children who like their

parents a lot, and the parents love their kids a lot. We can't keep

having the image that it doesn't work rammed down your throat all the

time, because it might be making it not work, be a part of the reason

it's not working.

MOT: It seems like you have it all, Steve...

SH: Well, I must say I'd love to break

that illusion, because I could say I've got everything but the girl,

because my wife has got her place she wants to fulfill for the

children. She doesn't want to flit on an airplane every week to see me

play again. In fact, she's seen Yes play most probably more than

anybody you can think of, and yet she doesn't really need to see the

next Yes show. She knows exactly how good it can be, because she saw

it all the time in the '70s. So she's got great memories, and some of

them are very emotional memories, and I respect Jan completely for her

decision to come and see us whenever she wants to. But she's had so

many opportunities that one wouldn't expect her to want to take all of

them (laughs), but to make up for that, of course our children have